Tax Day Question: Can I Make Enough to Pay for Childcare?

When our daughter was born, my husband had just started his second year at a law firm and I had just been laid off from a part-time job. We sat down together to decide whether I should look for a new job or not. The question we asked ourselves was, “Could I make enough to pay for childcare?” If not, we reasoned, it would make sense for me to take care of our baby myself.

Little did we know that the question had nothing to do with the cost of childcare and everything to do with tax policy.

You see, before World War II, the United States used an income tax system of separate filing for married couples in which tax rates applied to each spouse’s income separately.* As Ed McCaffery, author of Taxing Women, explains in his book, when the war ended and the costs of war went away, Congress saw an opportunity to reduce taxes. They did it by eliminating separate filing and replacing it with mandatory joint filing for couples. At the time, Congress also had an interest in wanting families to return to normal. In other words, they wanted mothers who had entered the workforce during the war to go back home. Joint filing would encourage them to do just that. As the legislative counsel of the treasury at the time remarked, “Wives need not continue to master the details of . . . business, but may turn . . . to the pursuit of homemaking.”

Joint filing introduced what McCaffery calls the “secondary earner bias.” The one who earns less, even today usually the woman, will be taxed more, which acts as a powerful but unseen disincentive for her to be employed.

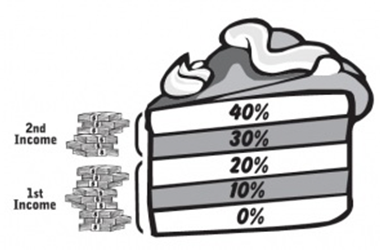

How does it work? Married couples filing jointly are required to combine their incomes, no matter who earns what. However, the money doesn’t go into a common pool that is all taxed at the same rate. As my friend Kimberly Tso explains in her blog post at The Two Penny Project, “Our federal income tax system uses graduated marginal rates. This is how to think about it: Imagine each dollar that you earn is stacked one on top of the other. Next, picture a large wedding cake next to the stack of dollar bills. Each tier of the cake (called the tax bracket) has a corresponding tax rate that increases as you go up each tier. …You only incur the higher tax rate if your stack of bills reaches that layer.” (See picture for example using hypothetical tax rates.) The policy goal of taxing the top layers more is for individuals who earn more to pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes compared to those who earn less.

For a couple, combining the incomes into one stack and then applying increasing rates to each layer has another effect—the secondary earner bias. When my husband and I faced the question of whether I should find a job or not, we thought of his job and his income as primary because he already had a job and he earned more. So we also thought of his income as first in the stack—where it would get taxed at lower rates.

My income was secondary. We could decide whether it was needed or not. We thought of childcare as coming out of my income because we wouldn’t need childcare unless I was employed. The question became, “Can I make enough to pay for childcare?” But the answer had everything to do with taxes. Given the combination of joint filing and graduated marginal rates, the very first dollar I earned would be in a layer on top of his income where it would get taxed at a higher rate. Subtracting childcare and that higher tax rate from my potential income, there wasn’t much left. Working for pay didn’t pay much. So we decided I wouldn’t, because we could afford for me not to. The World War II era policy worked on us precisely as it was intended.

McCaffery also explains that the secondary-earner bias influences mothers’ decisions and family finances at all income levels, not just for those who can afford not to be employed. Middle-income families who have a harder time giving up even the small contribution of a second earner face a “full-time or nothing” decision about employment. Working part-time just isn’t worth it. At even lower income levels, the wages of a second earner can put a couple over a threshold that means the loss of a tax break called the earned income tax credit. At these income levels—typically a household income of less than $40,000 a year—the secondary earner bias is even greater. If these parents work more, or if they aren’t yet married and then get married, they see little gain and may even lose money.

A policy decision made over 60 years ago continues to work as designed, invisibly, to discourage women from employment and lead mothers to ask themselves, “Can I make enough to pay for childcare?” Today there are those who claim women are “opting out” of the workforce or earning less because they “choose” to leave jobs to care for family but those people conveniently ignore – or are ignorant of – the fact that our tax policy was intentionally designed to push women out of the workforce.

Awareness of the secondary-earner bias can help families shift their thinking. My husband and I now talk about childcare as a family expense, not as his or hers. However, there’s no escaping the rational economic calculation unless we change the policy itself. Most advanced countries today mandate separate filing like the United States did before 1948. There are multiple policy options available to decrease the impact of the secondary earner bias. It doesn’t have to be this way, and it’s time to put more money in the pockets of families that need it and stop allowing this antiquated policy to push women out of the workforce.

More Resources:

- Women’s eNews “Tax Law Pushes ‘Secondary Earners’ to Drop Out,” Kristin Maschka

- Taxing Women, Ed McCaffery

- National Center for Policy Analysis: Women and Taxes, Ed McCaffery

- Further references for information in blog post available in This is Not How I Thought it Would Be: Remodeling Motherhood to Get the Lives We Want Today by Kristin Maschka, Chapter 10.

* The pre-World War II separate filing shouldn’t be confused with today’s “married, filing separately” category, which is used in rare circumstances, such as when one spouse wants to avoid the tax problems of the other.

[…] Kristin Maschka is the author of the LA Times Bestseller, This is Not How I Thought It Would Be: Remodeling Motherhood to Get the Lives We Want Today. This piece is cross-posted from her blog. […]

Hi Kristin. Interesting post.

Just for completeness’ sake, the same drawback exists if it’s the husband deciding whether or not to work, right? Or are there female-specific tax code policies mentioned in the book (besides the obvious, like gender-based income gaps–I know you’ve written about that before). It seems to be more common for men to stay home today than it’s been in the past. Ironically, I always considered day-care to be a subsidy intended to increase the workforce and thus a society’s ability to compete, though maybe it was only your circumstance that made it not enough of an incentive.

I’ve always interpreted the tax benefit for being married (actually, depending on the circumstance there can be either benefits or penalties) as a way to incentivize hemlock, um, I mean wedlock.. Obviously, our culture has mostly had an historical bias for marriage, though this changed a bit in the 60’s (and 70’s, I guess?). I was just reading last night how some people believe one of the unintended impacts of the more radical aspects of the feminist movement is the high rates of out-of-wedlock births we have today (over 40% nationwide and as high as 72% for certain subgroups for example (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_01.pdf)). To be honest, I think the concern is more that those are single-parent households than non-married dual-parent ones. In any case, I am not surprised that society would want to incentivize marriage, but I am surprised that it would want to disincentivize dual-income households, at least from an economic standpoint. If we are doing so from a moral standpoint then that might make more sense.. though we are rarely so intentional or forward-thinking in our policies..

On a related note, recently I was reading a study that implied that single earner households are more efficient with money over and above the simple income and taxation issues. Specifically they tend to save more and are more financially organized in spite of the lower income.

Hi Mike –

Yes, the same drawback exists regardless of gender. Husbands who are secondary earners face the same secondary earner bias. But even today the majority of secondary earners – those making 40% or less of a couple’s income – are women. Especially in families with children. The original intention of the policy was gendered – they wanted women to leave the workforce and leave the jobs for men returning from the war. The policy today has the same gendered impact because of mothers in particular still struggle to fit into a workforce designed largely around the way men worked in the 1950’s – with a wife to take care of everything else.

The number of stay at home dads is increasing, and a welcome trend – especially for busting stereotypes about men’s ability to care for family, but is still very small. 158,000 in 2010 compared to 5.1 million mothers who were not employed in 2010. The media tends to focus on the increase in SAHD precisely because it’s counter-stereotype for men and that gives the impression that the trend and number is bigger than it actually is.

As for childcare, very little of it is subsidized. The lowest income workers get some subsidy for childcare but because it’s so little and good care is so expensive, they are far more likely to rely on family and neighbor tag-teaming rather than opt for what can often be pretty bad care. The highest income workers often have access to a dependent care savings account through work so childcare costs are at least “tax free.” That leaves most families with pretty high childcare costs and little to no help with that cost. That childcare cost is one of the reasons families today have less disposable income than single earner families of the 70’s.

Thanks for chiming in on this. This secondary earner bias thing sticks in my craw and so few people know about it or know that it was designed 60+ years ago to do exactly what it is doing. If we really wanted to give a useful tax break right now, we’d get rid of it and at the same time figure out a way to decrease childcare costs for single-earner families as well.

Kristin